The Peter Principle Revisited

Variance and Promotions

The Peter Principle

The Peter principle is a famous observation that employees in an organization keep getting promoted until they are incompetent. Since being good at your current level means you will get promoted, the only reason you wouldn’t be is if you are incompetent. Therefore in the limit everyone in an organization appears to be incompetent. It can be illustrated in this simple chart:

Since employees are almost never demoted, this leads to a terrible situation in which the employer has poor employees in each role and those employees are also miserable because they are not performing. Or so the initial idea goes.

Improvement

Let’s take a closer look at the chart. Surely it’s not realistic to expect no improvement in true skill. Initially we expect skill to improve quickly, then slower and slower as you progress in your career. So the picture might look more like this:

We’ve apparently reached the same problem. But if you continue to improve you’ll see that eventually you’ll actually become competent even at your new level:

Of course at this point there might be another promotion. But perhaps not, for perhaps the employer has identified based on your lack of success initially that this is as far as you’ll go. So it appears that through improvement you can bypass some of the issues of the Peter principle. But this isn’t the full story.

Trailing Promotions

To diminish the impact of the Peter principle, many organizations base promotions on your potential success at the next level, rather than your current success (this might be called “trailing promotions”). To update the chart, we get a situation like this:

Here we see that the dotted line represents a potential promotion. It will only be enacted if the employee actually meets the bar. In this case they don’t, so the promotion is not carried out. Eventually, if the skill level increases, then there will finally be a promotion:

This can lead to some frustrating experiences for employees, since they had many quick promotions initially they might come to expect them later, when this is not realistic. This can make people feel like they have “plateaued”, when in reality they are still improving, just at a much slower pace.

This process seems like it solves the problem completely, and so therefore there’s no reason for anyone to talk about the Peter principle anymore. Right?

Variance

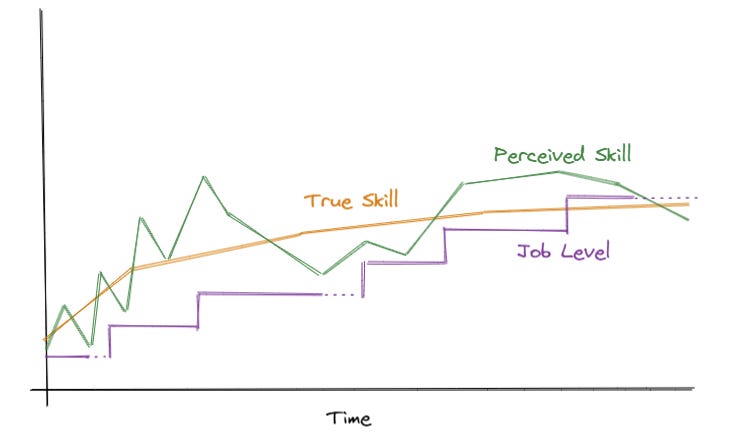

One issue with all the charts above is they assume that the employer has an accurate picture of someone’s “true skill”. In reality this is impossible. They will only get a very fuzzy picture of the person’s accomplishments, and must use that to infer true skill. The evaluation process is filled with all sorts of noise and biases that can affect the judgment. And accomplishments may depend on factors such as motivation and luck. So in reality it looks something like this:

Here we see some effects of the noisy judgment of skill. Initially there are periods where the employee should have been promoted, but because their skill was judged too low, their promotion was delayed. Then in the middle this mostly corrects. But at the end of the chart we see the opposite–because their skill was overrated they got promoted past their true skill again. The Peter principle has returned!

With the high variance present in any evaluation of performance, there’s no way to avoid the Peter principle. Even the “trailing promotions” strategy will fail in the presence of variance.

A Way Out?

What’s our way out of this predicament? There’s no perfect solution. The only option seems to be some form of demotion, but this is very unpopular and can hurt morale. One variant of this is “demotion via transfer”, in which an employee transfers to another role or department, so that it won’t be obvious to their coworkers what happened. But this likely won’t be welcomed by everyone. Another “solution” is finding a new job (either voluntarily or otherwise).

Employees with high self-awareness might realize that they are performing above their true skill, and could decline a promotion in that case. Unfortunately there’s no reason to think that they can evaluate their true skill any more accurately than others can (many are subject to impostor syndrome or the Dunning-Kruger effect). In summary, if we aren’t willing to consider reversing course, then because of variance we’ll always overshoot. Similar to the “winner’s curse” in auctions, basing any decision on the peak of variance will end up with a regretful outcome.